I avoid dancing at weddings, playing softball at picnics, exercising in group classes and other public displays of physical coordination. It’s not merely that I’m embarrassed by my lack of grace and rhythm. I want to avoid the injury and mayhem that resulted in the past — broken bones, black eyes, and tripping and falling into an African drum band.

So I was unsure if a book about creativity by Twyla Tharp, one of the world’s most notable choreographers and dancers, would speak to me.

But “The Creative Habit” has an intriguing premise that mirrors one of my own deeply-held beliefs—creativity “is the product of preparation and effort, and it’s within reach of everyone who wants to achieve it.” And it is an inspirational reminder that no matter your natural-born talent, creativity takes a lot of practice and continual hard work.

Tharp shares dozens of specific ideas for how to stimulate creativity and produce creative work including practical exercises that anyone can apply, no matter their craft.

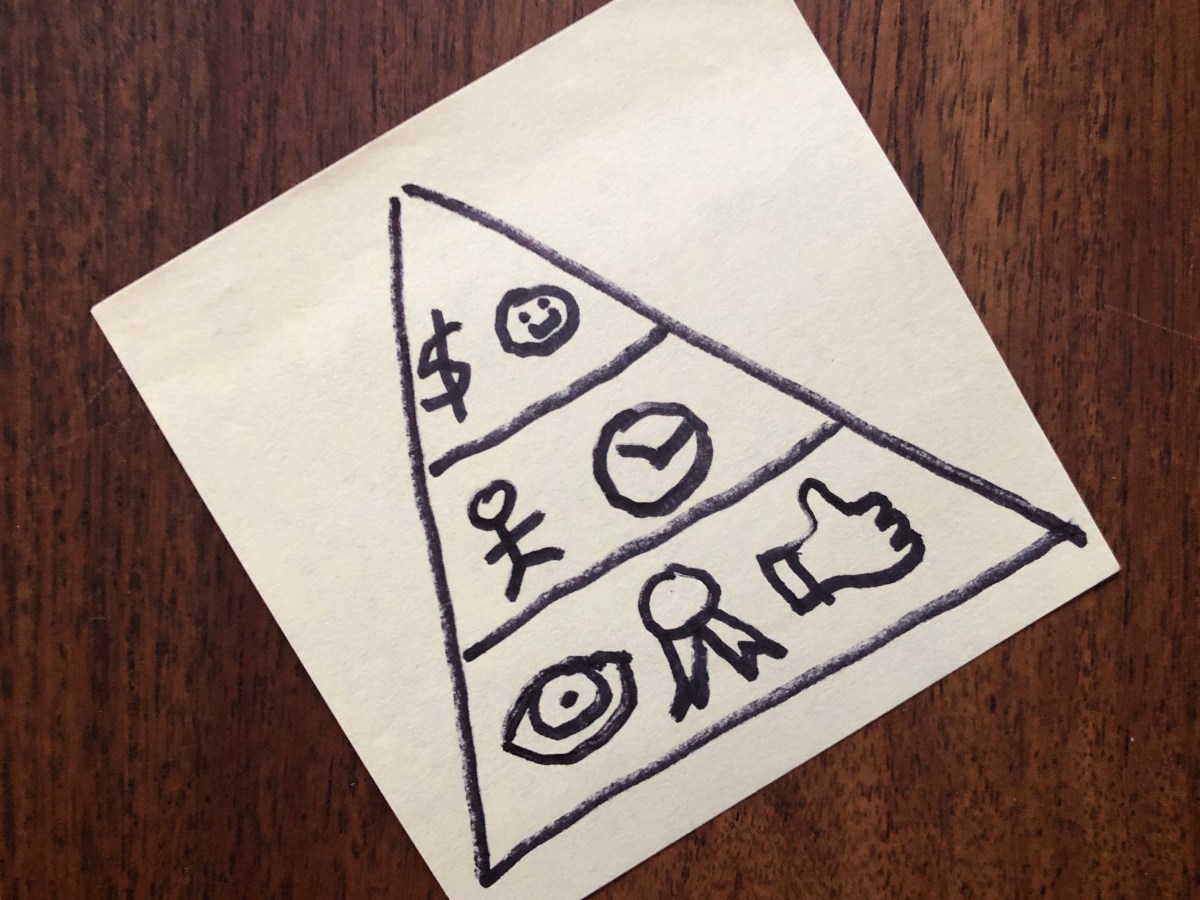

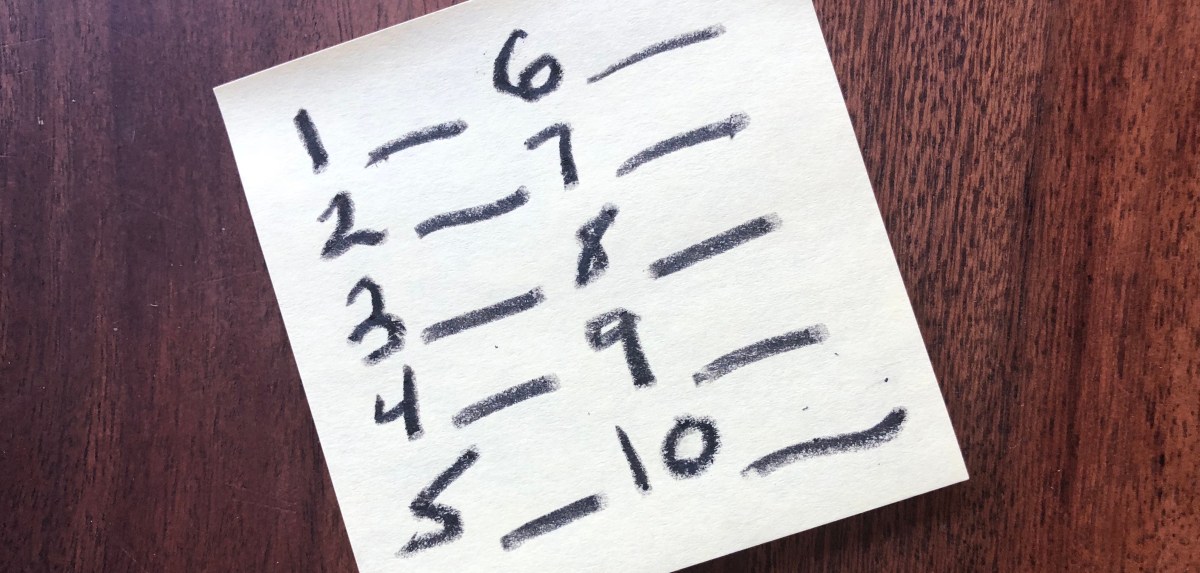

Here are three key takeaways:

1. Establish a Good Start-up Ritual

The first obstacle to creativity is fear. Fear of the empty stage, white paper, blank screen. Fear leads to distractions, procrastination, and paralysis – all excuses to avoid doing something that might fail. But it is also the barrier to doing anything at all.

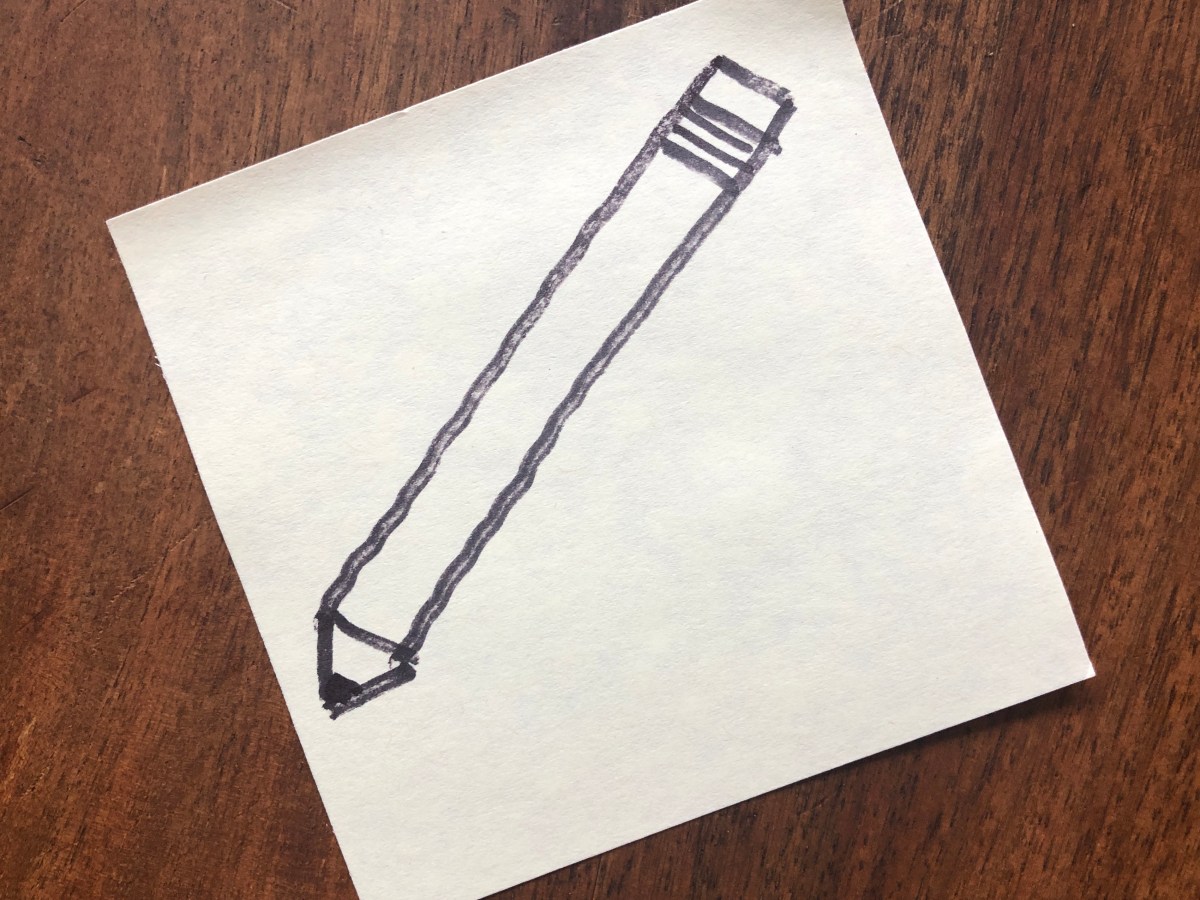

A good start-up ritual immediately bypasses those fear-generated obstacles and prepares you to do the hard work creativity requires. Tharp tells the story of the writer Paul Auster never leaving the house without a pencil. As a kid he always wanted to be able to get an autograph. But he credits that simple habit as being the reason he became a writer. He says, “if there’s a pencil in your pocket, there’s a good chance that one day you’ll feel tempted to start using it.”

Instead of putting a pencil in your pocket you might say a mantra, visit a place, or do an activity. But the point is to develop and stick to a “start-up ritual that impels you forward every day,” bypassing obstacles and entering a receptive, open state of mind ready to capture the first spark of an idea.

2. Think Small to Think Big

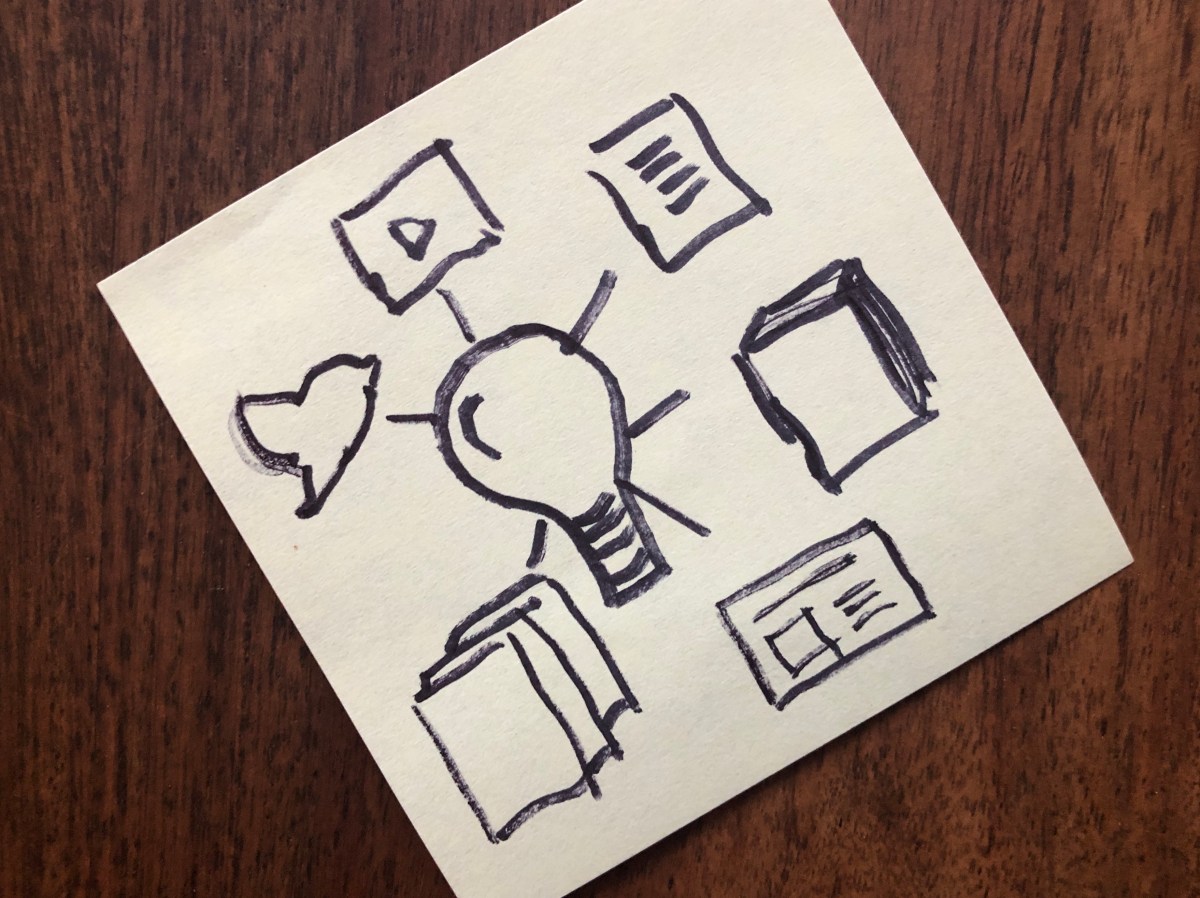

Sometimes, in spite of your diligent preparation, the Big Idea doesn’t come when you want it to. So Tharp recommends “scratching” for little ideas that might trigger the beginning of a larger one. The trick is to first immerse yourself in references, materials, and experiences that interest you. The goal is simple: uncover the smallest idea that inspires you to start working and the rest will follow.

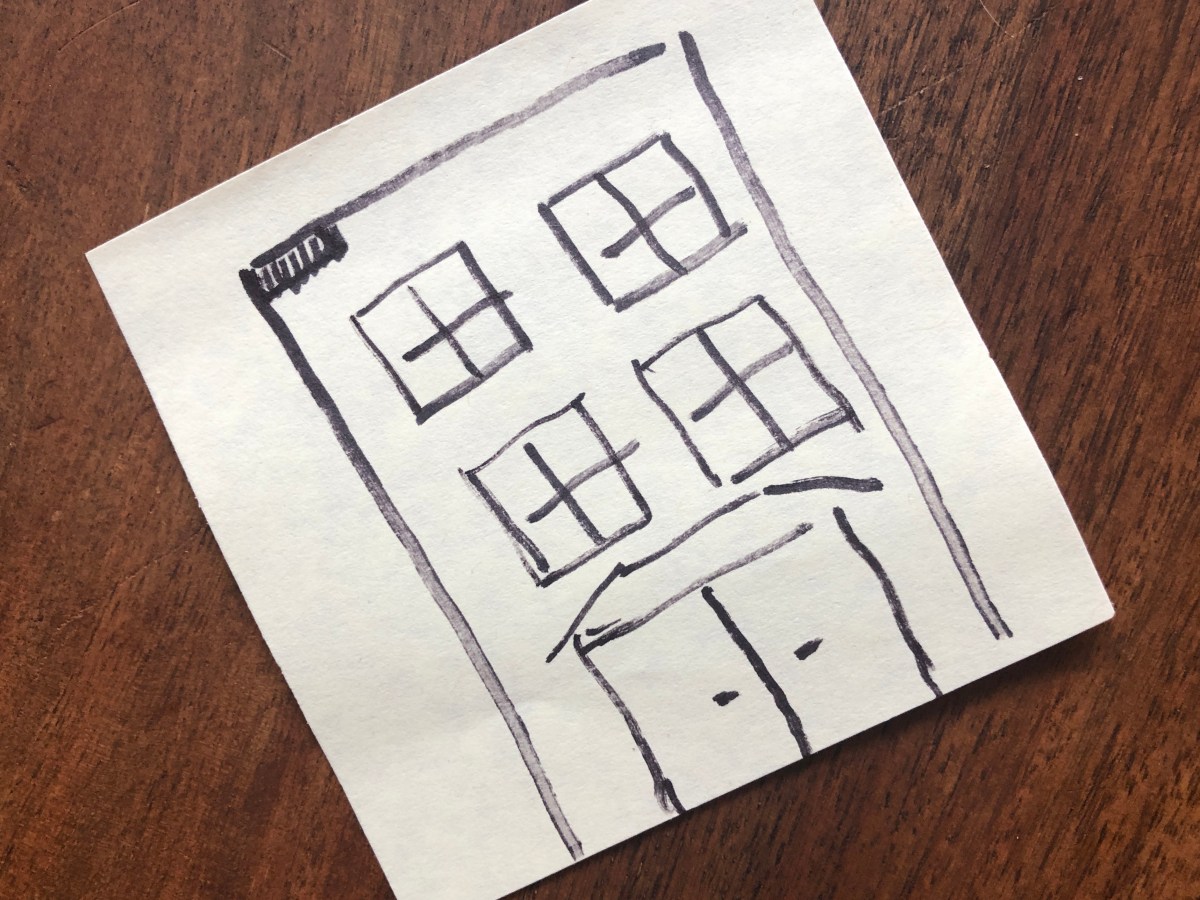

Tharp illustrates her point by including a story Robert Pirsig tells in his book, “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.”

When Pirsig was teaching a university course in Montana he had a student who struggled to complete an essay about the United States. He advised her to focus on something smaller — their hometown of Bozeman. When she was still stuck, he suggested the town’s main street. Finally, out of anger and frustration, he told her to “start with the upper left-hand brick” of the opera house on that main street. That worked! Afterwards she said she “started writing about the first brick, and the second brick, and then by the third brick it all started to come and I couldn’t stop.”

3. Be Prepared for Luck

You need to know how to prepare to be creative. But you also have to be prepared to be lucky. Meaning, you have to be ready to let go of your plans so you can seize the happy accidents that will transform your work into something more.

One of Tharp’s rules for “scratching” is a great example of how good creative habits prepare you to be lucky – she says to always scratch for more than one idea and then look for ways to combine them. “Luck” may take the form of a perplexing contrast, unexpected intersection, or poetic metaphor that launches a brand new area of exploration.

In spite of years of high-quality arts education, my teachers never taught me a process for coming up with ideas. They taught me how to talk about ideas and craft them. But they expected that my ideas would come purely from talent and inspiration, not discipline. I now realize how odd and disappointing that is.

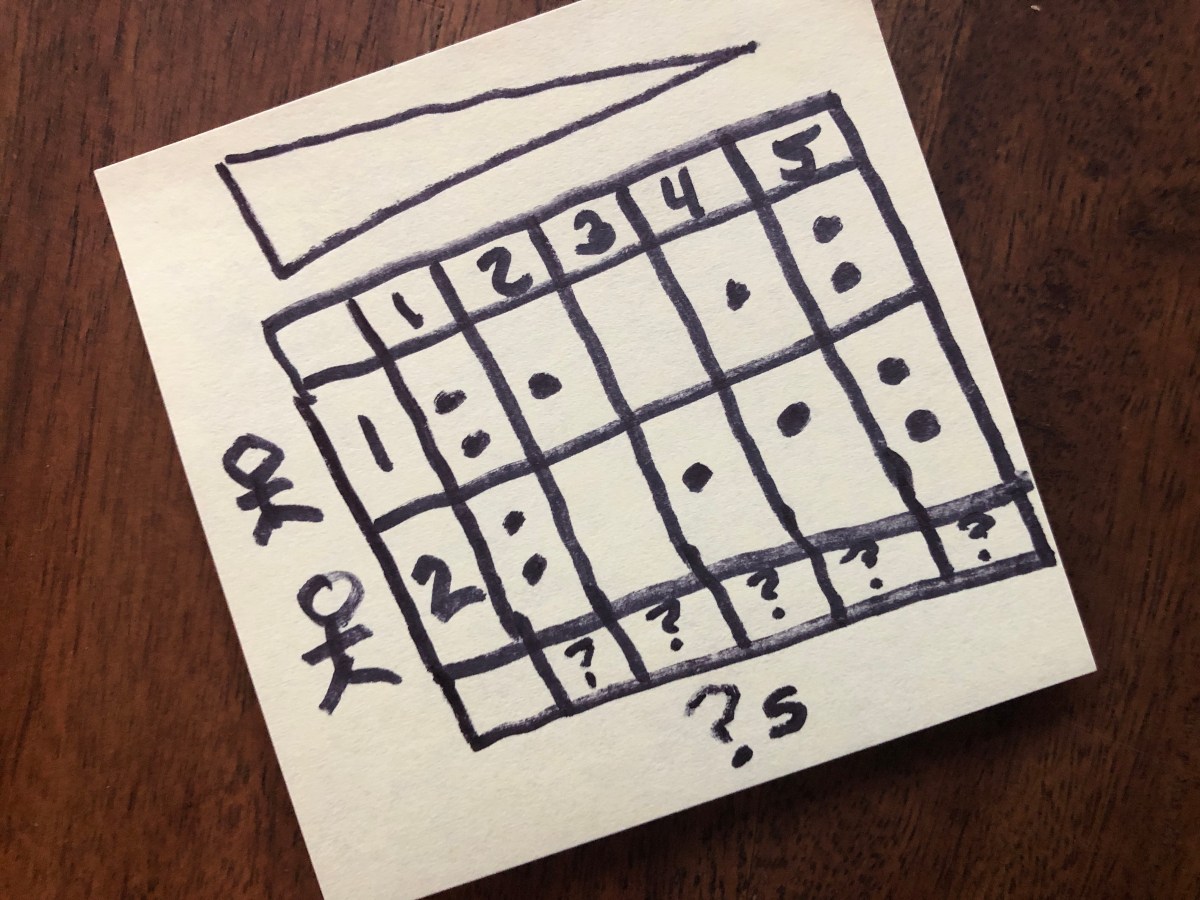

That’s probably why one of the most profound professional experiences I’ve had was documenting my team’s creative process and then teaching it to others. I developed that process over years and decades of life experience, trial and error, and the valuable input of other creative people who had already successfully done the same.

“The Creative Habit” is accessible, universal, and practical. Tharp is refreshingly transparent and generous in sharing her own creative process. Her ideas are applicable to any creative discipline. And her exercises support and strengthen any creative pursuit.

I only wish I read it sooner—and it taught me to dance a little better.

I want to remember what I read. So I doodle key takeaways on Post-it® notes and stick them to my wall. Hunting for the ideas keeps me engaged, doodling them is fun, and looking at them later makes me feel good. I figured: Why not share them?